Eye-surgery laser could be adapted for other organs, say scientists

Scientists in Scotland have shown that a type of laser already similar to the one currently used in routine eye surgery could one day help surgeons remove unwanted tissues, such as tumours, with unprecedented accuracy.

Researchers at Heriot-Watt University and the University of Edinburgh have carried out one of the most detailed studies to date of how deep-ultraviolet, ultrashort-pulsed lasers interact with soft biological tissue.

These lasers can remove tissue in slices as thin as 10 micrometres, which is far finer than the millimetre-scale precision currently possible in neurosurgery.

This work is a stepping stone - we used a model that allowed us to run hundreds of tests and establish exactly which laser regimes might work on soft tissue like the brain

The research was undertaken as part of the multidisciplinary u-Care project funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

The findings have been published in Biomedical Optics Express.

Softer tissue presents challenges

The same principle has been used for around 30 years in eye procedures such as LASIK, where surgeons reshape the cornea using tightly controlled pulses of ultraviolet light.

The top layer of cells absorbs the ultraviolet light and blocks it from going further into the tissue. When the laser fires in ultrashort pulses, these cells are instantly evaporated, without damaging the surrounding tissue.

Tatiana Malikova, a PhD student in Heriot-Watt’s School of Engineering and Physical Sciences, led the study.

Tatiana said: “The cornea is well suited to this technique because it is rigid, collagen-rich and the eye’s surface is easy to reach with an ultraviolet laser beam.

“There have been hardly any studies on how it might work in softer tissues, like the brain.”

Tatiana and her colleagues used supermarket-bought lamb liver as a stand-in for brain tissue in their study.

“It’s mechanically weak and soft, although not as fragile as the brain.

"However, brain tissue samples are very hard to get, and we wanted to run a large and tightly controlled study to understand how the laser behaves with challenging soft tissue.

“Our end goal is to make future brain surgery more precise.

"This work is a stepping stone - we used a model that allowed us to run hundreds of tests and establish exactly which laser regimes might work on soft tissue like the brain, and why."

Tissue left undamaged

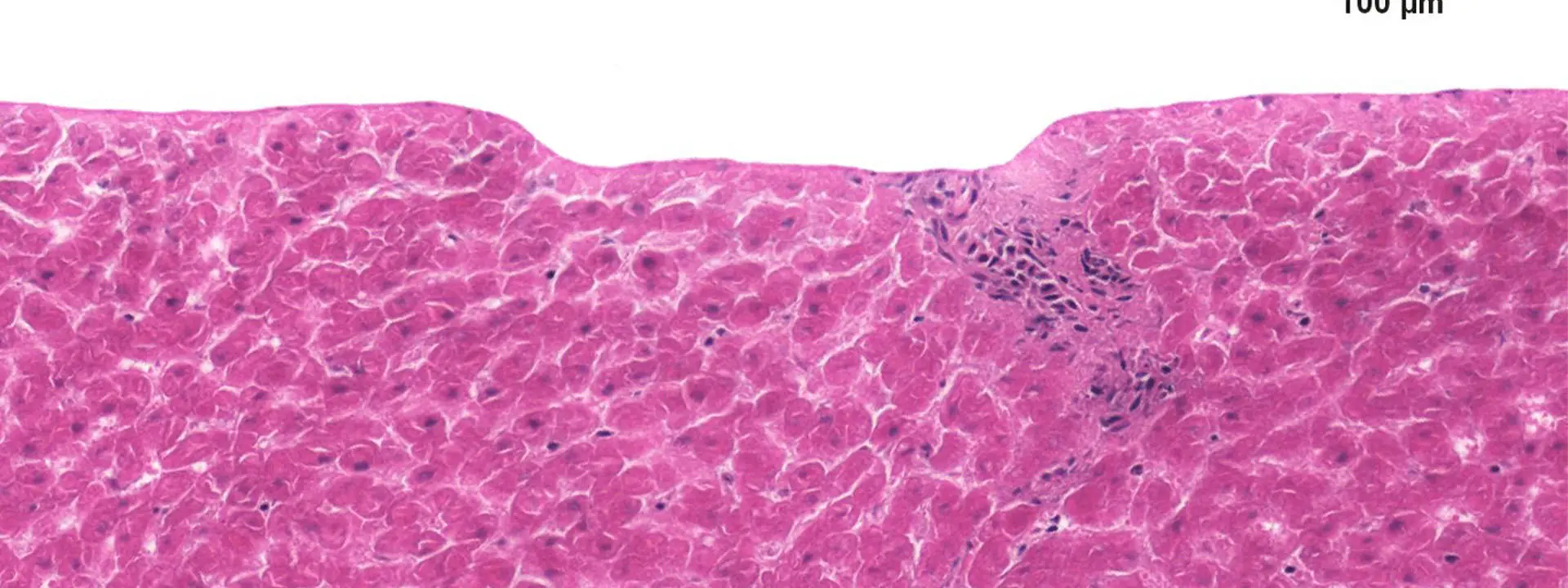

She says the study stands out due to the level of detail in the measurements, including extensive histology, where tissue samples are examined under a microscope.

“Thirty years ago the imaging was not good enough to see the effects clearly. Now we can show an entire array of high-quality images.

"We have demonstrated 10-micrometre precision with no detectable collateral damage. I am confident we can go even finer than that."

The team achieved clean and controlled tissue removal with an axial precision of around 10 micrometres using a 206-nanometre, 250-femtosecond laser system. Under the right conditions, the tissue surrounding the ablation zone showed no damage.

In neurosurgery, where a few millimetres can determine whether a patient recovers or suffers a lasting deficit, this advancement could be game-changing.

Although neurosurgeons already work with great accuracy, Tatiana says the potential of deep ultraviolet lasers far exceeds what is currently possible in a theatre.

“Neurosurgeons are very precise, but their precision is on the millimetre scale.

"Getting to 10 micrometres, which is 10 times finer than a human hair, is not realistic with current tools.

“In the coming decades, as imaging and robotic guidance become standard, all of these technologies could come together.

"Then I think a system like ours could fit into the surgical workflow.”

Laser-based tools have already vastly improved eye surgery and the researchers believe that similar advances are possible in neurosurgery once the precision of deep ultraviolet lasers is fully understood across different tissue types.

Within the next few decades, laser technologies like this could transform surgery and improve patient outcomes

Paul Brennan, Professor of Clinical and Experimental Neurosurgery and Honorary Consultant Neurosurgeon at the Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, said: “The accuracy of current surgical tools when working close to critical structures affects the precision and safety of surgery.

“The ultrafast laser approach promises a level of precision that could transform the way we treat intracranial tumours.

“In neurosurgery, where a few millimetres can determine whether a patient recovers or suffers a lasting deficit, this advancement could be game-changing.”

Paul is part of the u-Care project team and has been consulting on the potential applications of deep-ultraviolet ultrashort-pulsed lasers in neurosurgery.

Robert Thomson, Professor of Photonics at the Institute of Photonics and Quantum Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, and primary investigator on the u-Care project, said: “This is exactly the sort of foundation that lets the field move forward.

“Within the next few decades, laser technologies like this could transform surgery and improve patient outcomes.”

U-Care aims to exploit cutting-edge techniques in laser physics to create deep ultraviolet light sources that are compact and robust. The project also plans to develop precise methods for delivering this light to the body, opening the door to therapies that tackle two major medical challenges: cancer surgery carried out with cellular-level precision and the growing threat of drug-resistant superbugs.