Ultrasound breakthrough can pinpoint cancer with precision

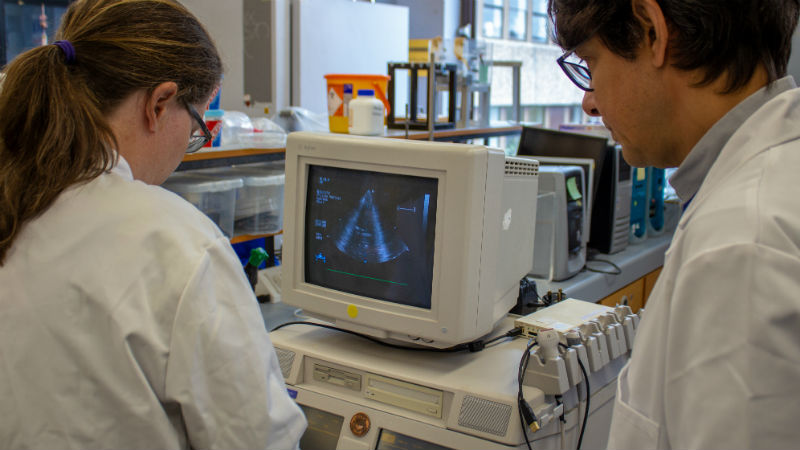

A team of scientists, led by Dr Vassilis Sboros, have unveiled a new cancer diagnostic technique using super-resolution ultrasound methods. The largest revolution in ultrasound technology in over 60 years is expected to lead to earlier cancer diagnoses and allow medical staff to target treatments more effectively.

What is ultrasound and how is it used currently?

An ultrasound scan, sometimes called a sonogram, is a procedure that uses high-frequency sound waves to create an image of part of the inside of the body. It is used in cancer diagnosis mainly due to its cost-effectiveness and unique real-time capability. However, due to many factors affecting current ultrasound scans, more expensive Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) are often used for diagnosis and treatment.

Which of these factors does your research addresses?

One drawback of existing super-resolution ultrasound imaging is that the person being scanned has to stay completely still for an unrealistic length of time during the procedure. Our new technique makes the imaging achievable in just a few minutes. Because it uses existing ultrasound machines, hospitals won’t need to invest in new equipment.

What does your technique do differently?

Our team demonstrated for the first time that prostate cancer can be detected by mapping the blood vessels that surround the cancerous tissue. This shows a different pattern to that of normal tissue. Biopsies are currently performed as a separate procedure to MRI or CT imaging, which is more expensive for the hospital and can be both disruptive and distressing for the patient. On the other hand, ultrasound imaging can be done at the same time as biopsies, and is often used to guide biopsy needles, but with limited success. Our new technique will aid, in the first instance, the biopsy procedure and, if proven successful, could replace biopsy altogether.

When and where will it start being used by clinicians?

Prostate patients at the Western General Hospital in Edinburgh will be the first to benefit. From December this year, we will work to establish the application of our method in a clinical trial.

What are your future research plans?

We hope that further research will help establish this method in diagnostic procedures. It should also be possible to help assess the effectiveness of cancer treatment more promptly. At present, this isn’t done until three months after the start of treatment, too late for some patients when the treatment is not working. We also aim to expand the remit of our method to early screening the population for a number of patients. Finally, the method may be applied to a number of other diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, liver disease, transplant rejection and others.

Key information

Vassilis Sboros

- Professor

- v.sboros@hw.ac.uk